Chapter 10: Spatial Dimensions of Heaviness

Width, depth, and immersion in heavy production.

Navigate Chapters

While previous sections have addressed tonal, dynamic, and technical elements of heaviness, this section explores an often-overlooked dimension: how spatial characteristics shape the listener’s perception. The research documented distinct approaches to spatial design that significantly impact the effectiveness of heavy productions.

Width: Beyond Pan Positions

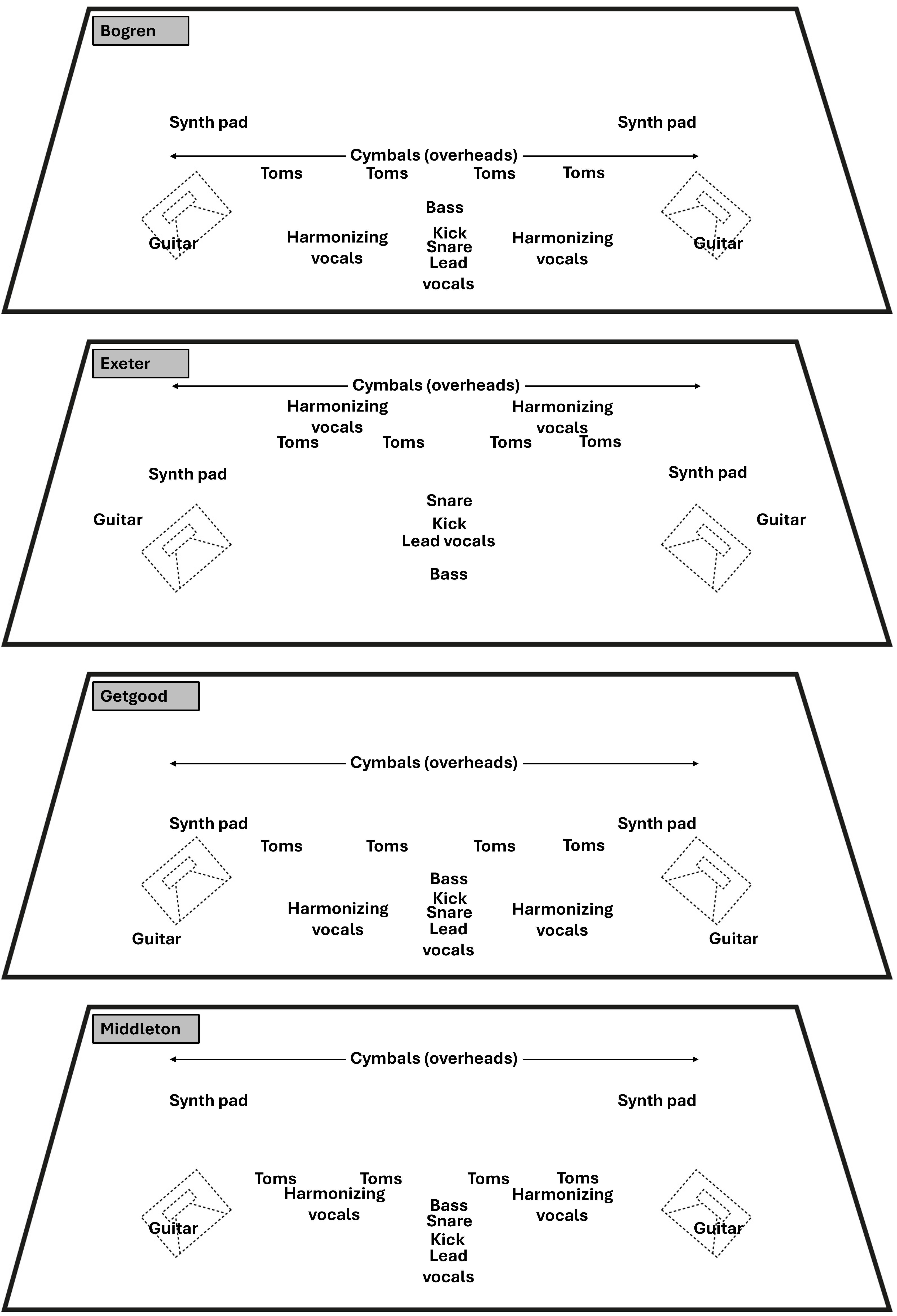

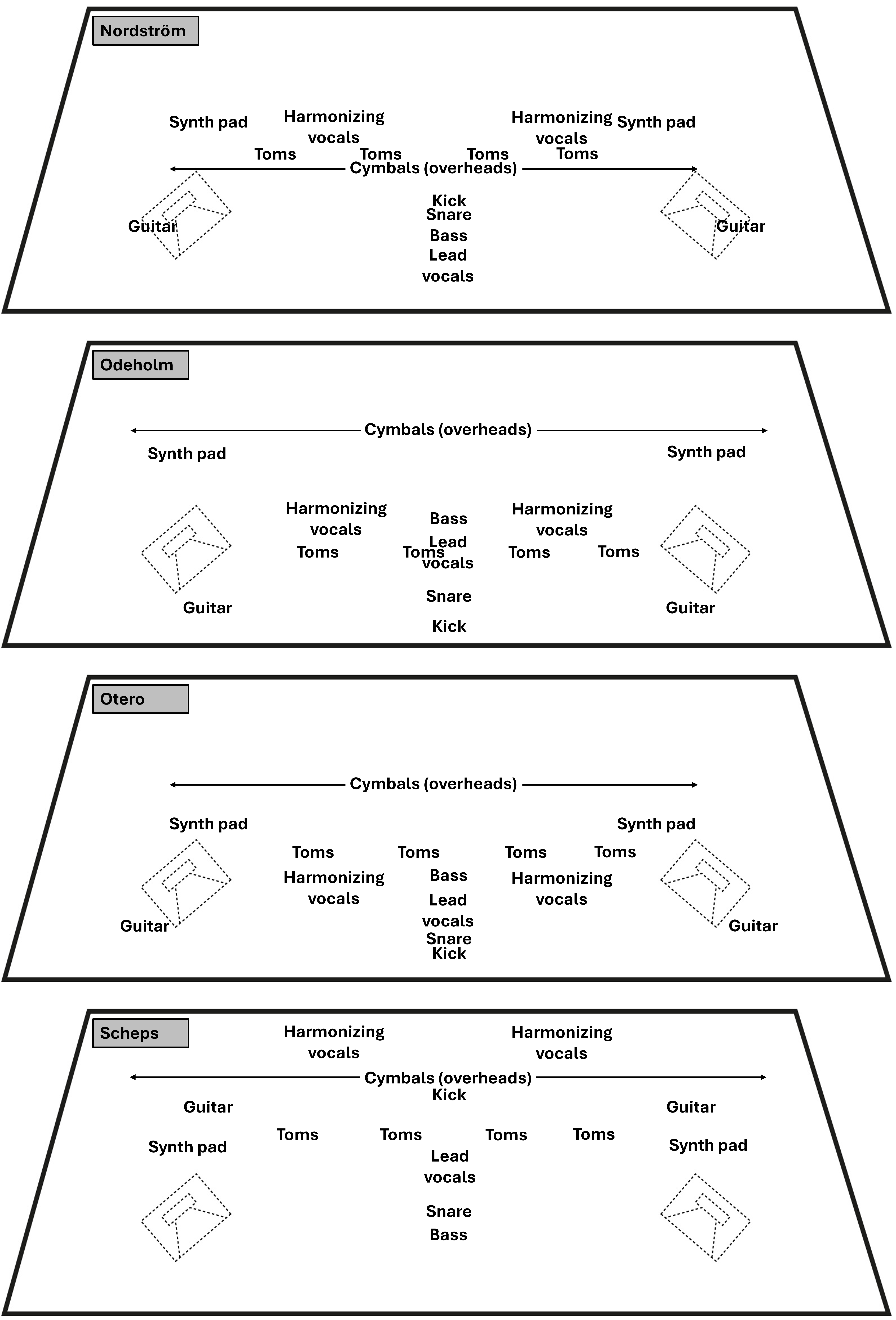

All producers employed stereo techniques to sculpt width, but with different approaches and philosophical underpinnings:

- Traditional Hard-Panning: The foundational approach to width in metal involves hard-panning rhythm guitars left and right. This technique, dating back to early metal productions, creates a wide stereo field while maintaining a strong centre presence through kick, snare, bass, and vocals. Jens Bogren, representing the traditional Swedish death metal sound, maintained this approach with minimal embellishment, creating a classic metal wall of guitars.

- Enhanced Psychoacoustic Width: Several producers chose sophisticated techniques to create width beyond what simple panning permits. Adam Getgood and Josh Middleton utilized stereo enhancement plugins1 that create phase differences between channels, resulting in a perceived width that exceeds the physical speaker placement. Middleton described the outcome as extending beyond the speakers to create an enveloping experience that surrounds the listener.

- Asymmetrical EQ Approach: Notably, the research found that Andrew Scheps and Mike Exeter achieved comparable width through a more transparent technique: applying slightly different equalization to left and right guitar channels. The brain perceives even subtle frequency imbalances between channels as increased width. This approach maintains phase coherence while still creating the impression of guitars extending beyond speaker boundaries.

- Extended Bass Width: Odeholm's application of the meta-instrument concept to spatial design (as described in Chapter 7) represents perhaps the most radical departure from convention. His stereo bass approach created a distinct spatial configuration where traditional instrument roles are inverted: bass contributes to width while guitars reinforce central impact.

Analysis of the ‘In Solitude’ suggests multiple valid paths to creating spatial staging, each with distinct tonal and phase characteristics.

Depth: From In-Your-Face to Three-Dimensional

The research identified depth perception as a central yet often overlooked dimension of heaviness, with approaches falling into several overlapping categories (Figures 10.1–10.2):

- Immersive Depth Staging: Several producers including Andrew Scheps employed a virtual soundstage concept where instruments occupy distinct positions in a three-dimensional space. In Scheps’s mix, backing vocals were positioned deep in the soundstage while lead elements remained upfront. This creates a believable space where the band exists, which enhances the perceived authenticity and depth of the production. This approach aligns with traditional rock production values, where creating a realistic performance space enhances listener engagement.

- Controlled Ambient Space: Jens Bogren and Mike Exeter created depth through selective reverb application, using multiple ambient layers. Bogren used up to four different reverbs on drums alone, each tailored to specific elements but sharing complementary characteristics. This creates the impression of a cohesive space while maintaining separation between elements. Significantly, even these ambient-aware producers kept reverb times relatively short (typically under 1.5 seconds) to maintain impact and clarity.

- Hyperreal Flatness: At the opposite extreme, Buster Odeholm minimized depth cues to create a direct transmission to the listener. By keeping elements extremely dry2 and upfront in the mix, he created the sensation of the sound bypassing space entirely; it is as if the instruments are physically present in the listener's space rather than captured in a recording. This approach sacrifices spatial realism for maximum impact and creates the impression of being physically confronted by sound.

The analysis suggested that depth perception influences how listeners experience the characteristics of the mix, including the perception of heaviness. Three-dimensional mixes create heaviness through immersion and scale, while flattened presentations ("in your face") achieve it through directness and confrontation. Both approaches prove effective but engage listeners in different ways.