Chapter 7: The "Meta-Instrument" Concept

Treating kick, bass, and guitars as a single, unified sonic entity.

Navigate Chapters

One of the most significant insights to result from the research was the concept of the "meta-instrument": a production approach that reframes how instruments interact in heavy music. This concept, while particularly prominent in hyperreal production, has influenced metal mixing across the spectrum and represents a paradigm shift in how engineers conceptualize heaviness.

Conventional vs. Meta-Instrument Mixing

Traditional Approach: Each instrument as a separate entity.

- Each instrument occupies its own frequency space and stereo position.

- Clear separation between elements (kick handles sub-bass, bass guitar covers bass and low-mids, guitars dominate the midrange).

- Focus on distinction between elements for clarity.

Meta-Instrument Approach: Instruments as components of a unified force.

- Guitars, bass, and kick drum function as parts of a single massive sound.

- Intentional frequency overlap with careful phase relationships.

- Coordinated dynamic behaviour across instrument groups.

- Focus on collective impact rather than individual clarity.

Technical Implementation

Implementing the meta-instrument approach requires specific technical strategies:

- Transient Alignment: The foundation of the meta-instrument concept is precise rhythmic alignment between instruments. Odeholm's sample-level editing approach (detailed in Chapter 6) represents the extreme application of this principle. Even slightly more conservative producers like Getgood and Otero emphasize the importance of aligned attacks for maximum heaviness, though with less microscopic attention to waveform alignment.

- Complementary Frequency Allocation: Rather than assigning completely separate frequency ranges and spatial positions to each instrument, meta-instrument mixing creates intentional overlaps while ensuring phase coherence1. Josh Middleton demonstrated this approach by high-passing guitars at just 70 Hz2, which allows them to carry significant low-end energy. He simultaneously cut around 180 Hz and boosted the bass guitar at 190 Hz to create a complementary frequency relationship.

- Unified Dynamic Behaviour: Meta-instrument production often employs synchronized dynamics processing across multiple instruments. Odeholm's approach of sidechaining3 both bass and guitars to the kick drum ensures the entire instrument group "breathes" together, ducking4 in unison when the kick hits and swelling back collectively. This coordinated movement enhances the perception of a single entity rather than separate instruments.

- Interconnected Processing Chains: The approach often integrates signal paths between instruments that traditionally would be processed independently. For example, several producers mentioned using a send from the kick drum to trigger a specific distortion characteristic on the bass or linking compressors across instrument groups. These interconnections create a cohesive texture where instruments enhance rather than compete with each other.

Spectral and Spatial Distribution

The meta-instrument concept manifests in unconventional approaches to both frequency allocation and stereo positioning:

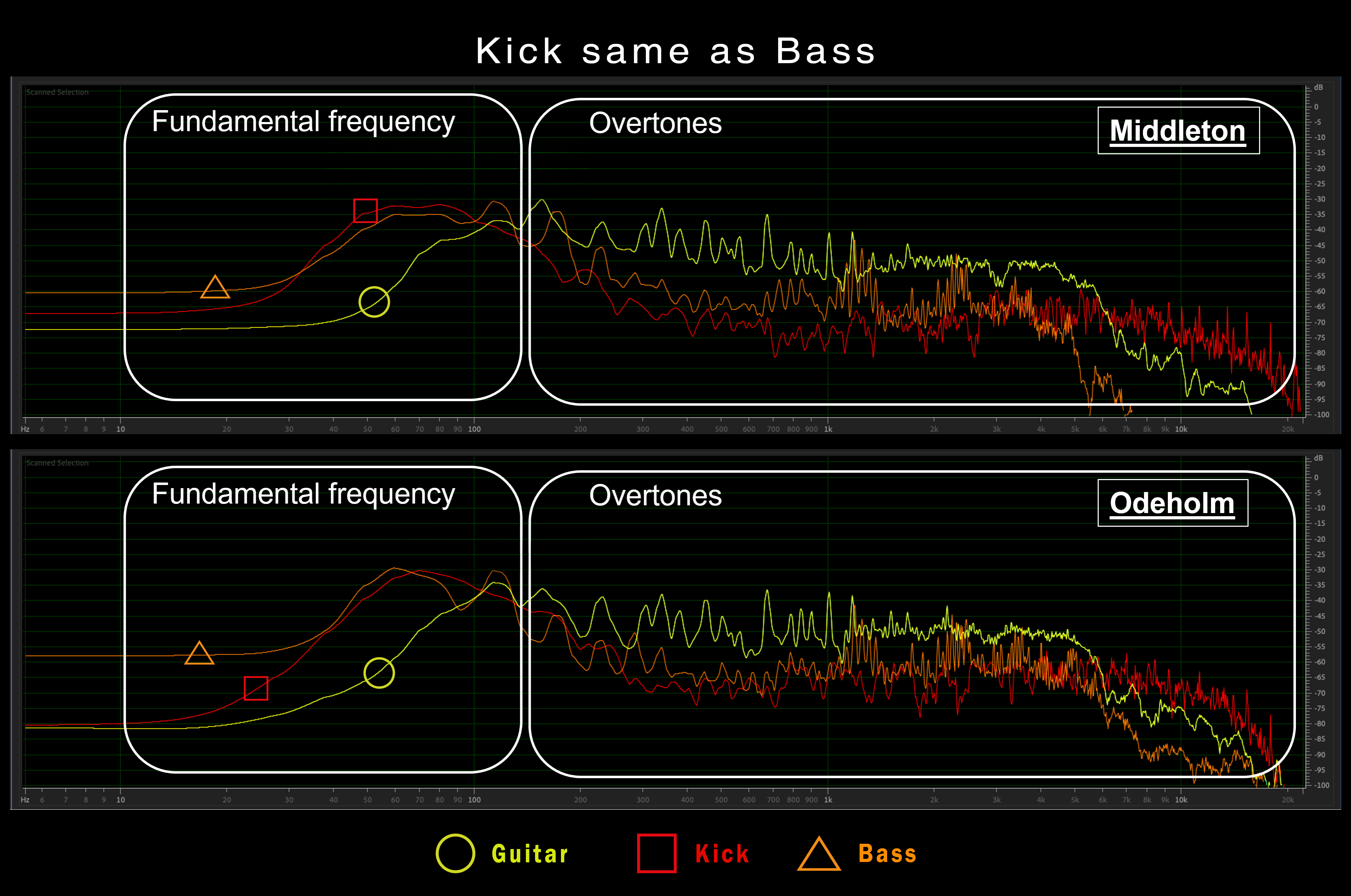

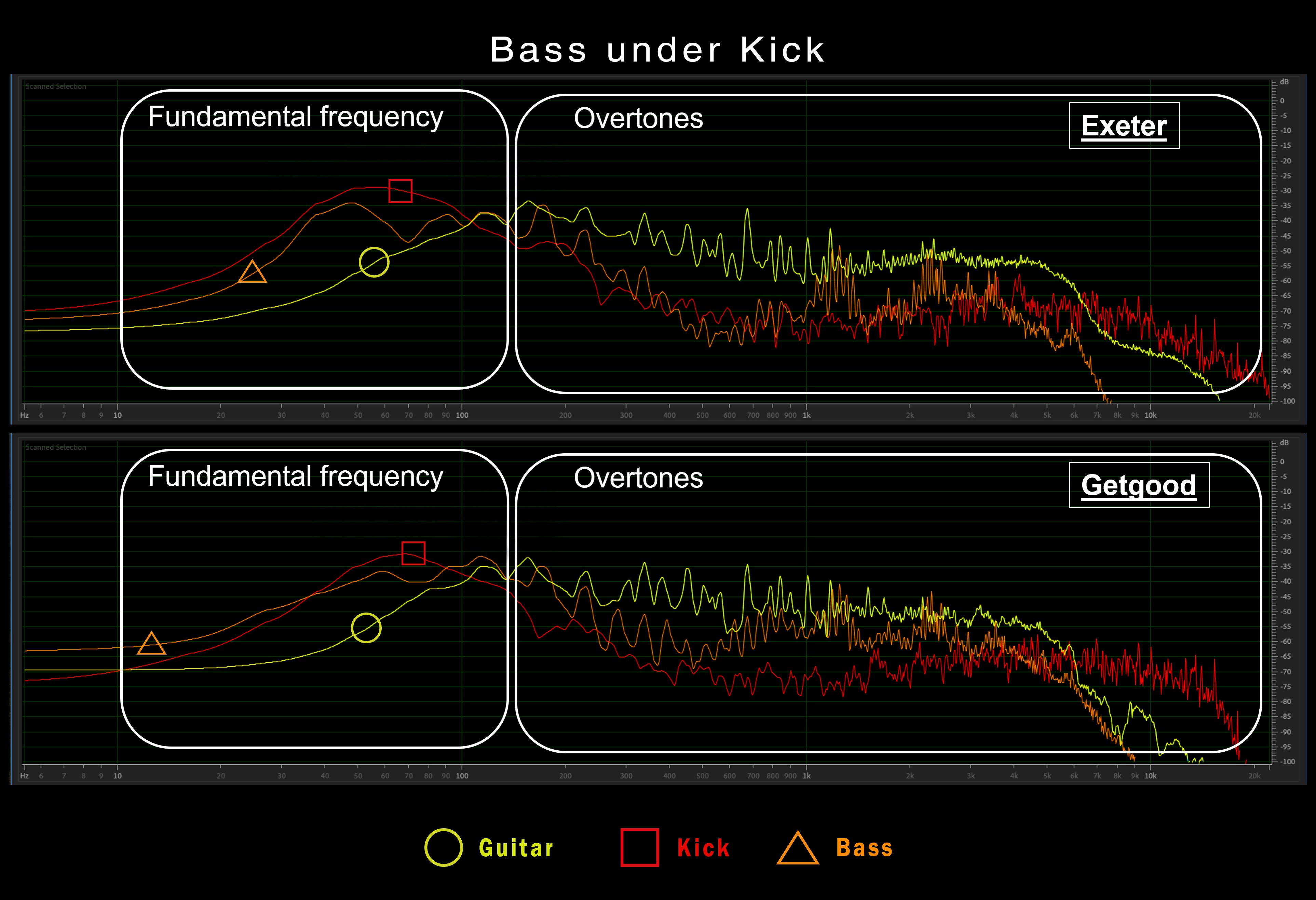

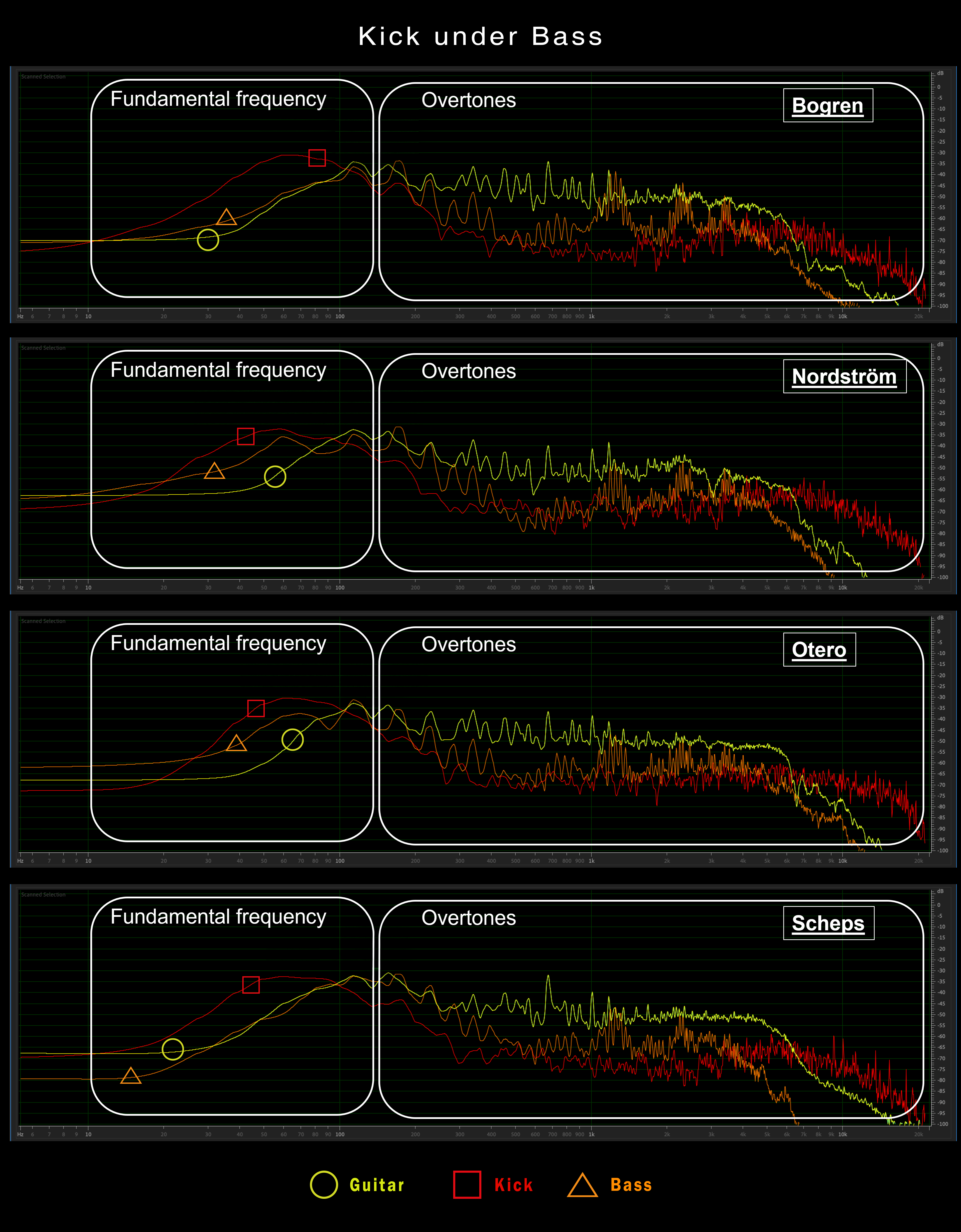

- Frequency Integration: While traditional mixing often high-passes guitars around 100 Hz to make room for bass, meta-instrument mixing might allow guitars to extend down to 60 Hz while carefully controlling their relationship with the bass guitar through phase alignment and dynamic processing. This creates an integrated spectrum where the listener cannot easily distinguish which instrument is generating specific low frequencies (Figures 7.1–7.3).

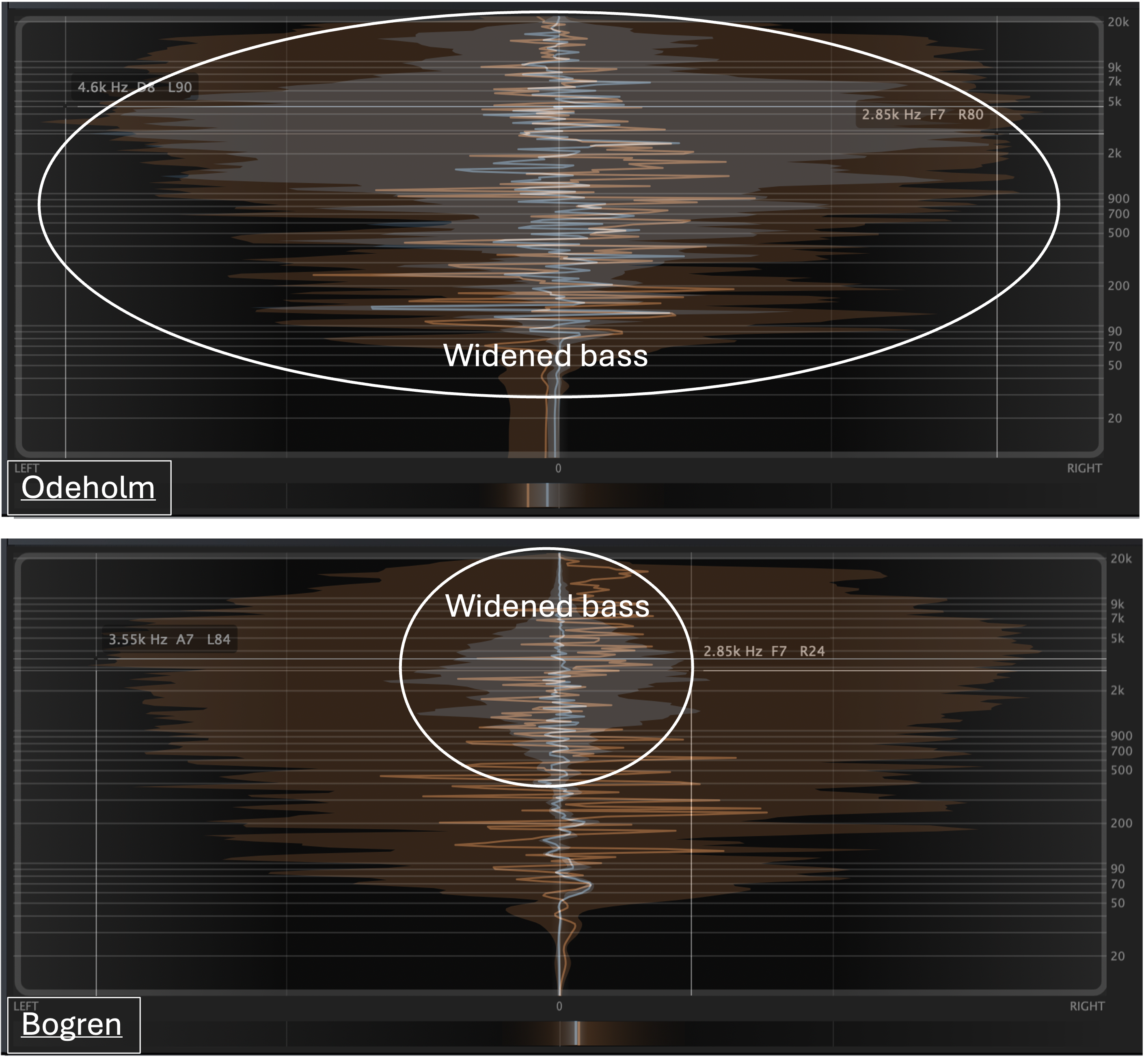

- Spatial Reconfiguration: Odeholm's approach of panning5 a guitar track in the centre while spreading the bass across the stereo field represents a radical departure from traditional placement (Figure 7.4). This technique distributes the meta-instrument across the entire stereo field while maintaining its unified impact to create what Getgood describes as a 'floor-to-ceiling sound'.

Variations Across Production Philosophies

While the meta-instrument concept reaches its logical extreme in hyperreal production, elements of this approach appear across the philosophical spectrum:

- Naturalistic Implementation: Even Exeter, the most traditional producer in the study, demonstrated meta-instrument thinking through his complementary EQ choices for guitar and bass and his strategic automation of elements to work together in specific sections. Rather than enforcing rigid alignment, he created natural cohesion through careful balancing and tonal matching.

- Moderate Application: Producers like Bogren and Scheps employed partial meta-instrument techniques, particularly in how they approached the kick and bass relationship. Bogren's practice of sidechaining the bass not just to the kick but also to the toms demonstrates systematic thinking about how these elements should function together as a unified rhythmic foundation.

- Full Integration: At the furthest extreme, Odeholm treated the entire instrument section as essentially one massive synthesizer, with each component carefully tuned to contribute to a singular sonic event rather than stand as individual instruments.

Impact on Heaviness

The meta-instrument concept addresses what many producers identified as essential to heaviness: the sensation of being confronted by an overwhelming force rather than discrete elements. By engineering instruments to function as a unified entity, producers create what Getgood describes as a mechanical yet musical quality: a sound that exceeds what humans could physically produce while maintaining musical coherence.

This approach particularly excels at creating the 'freight train rolling over you' type of heaviness that Josh Middleton described. This is a sensation of density and weight that physically impacts the listener. When implemented effectively, the meta-instrument creates a sound that physically embodies heaviness rather than merely suggesting it.

The meta-instrument concept raises questions about the nature of instrumental identity in modern production. While traditional approaches preserve the distinct character of each instrument, meta-instrument mixing deliberately blurs these boundaries in service of a greater sonic impact. This represents a fundamental shift from documenting a performance to engineering an experience. It is a development that continues to reshape how heaviness is conceived and created in contemporary metal.

'Get the band to sound like one unit... one big tank going forward'.

'That's when all the transients have to be at the same point. The guitar, bass, and kick drum have to hit exactly at the same time and be in phase, which is like samples of timing difference'.

'A lot of people say kick below or above bass or bass above or below kick. I never really think about it like that; I let the sources guide me'.

Endnotes

- Alignment of audio signals to prevent cancellation. ↩

- Using a high-pass filter that removes frequencies below 70 Hz. ↩

- Triggering effects on one track based on the volume of another track. ↩

- Lowering volume when another sound exceeds a threshold. ↩

- Controlling the position of a sound image between stereo speakers. ↩